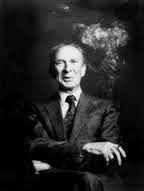

“Freedom and resentment” is one critical essay of Strawson,

which was originally delivered as a lecture to the British Academy and then

published in Proceedings of the British

Academy (1962).

Here he is...

In his paper, overall, Strawson argues the role and implications of determinism (assuming the possible truth of determinism) for agents susceptible of moral assessment. His main argument is that "pessimism" and "optimism" about the compatibility of determinism and morality needn't be mutually exclusive, that is to say, they can somehow be reconciled.

But how come? His argument about the compatibility of determinism and morality is further strengthened by his differentiation of attitudes as:

1. Reactive attitudes (such as resentment and gratitude)

2. Moral reactive attitudes

3. Self reactive attitudes

The key question in his essay is that if we assume determinism to hold true, would we have to assess everybody with an "objective attitude"?

According to Strawson "No!" because first of all, being a human renders reactive attitudes natural even under the case in which the agents are deemed to be free from responsibility (answerability, accountability) due to various reasons.

Likewise, in arguing moral attitudes, Strawson claims that believing determinism to be true does not necessarily lead us to "abandon moral dispprobation of agents."

In summary, he arrives at the general conclusion that the reasons of the fact that in some circumstances we need to suspend our moral reactive attitudes toward some agent doesn't entail the truth of determinism. Furthermore, rationality is not disputable for issues related to the very nature of human being such as having reactive attitudes.